Two misconceptions haunt water and sanitation. First, that integrity or corruption issues are massive and related to power structures beyond the sectors. Second that dealing with these risks is someone else’s job – someone in the compliance unit, or an external authority. Either way, why should sanitation practitioners do anything about it.

Three new publications highlight the responsibility and power of sanitation practitioners to address the significant integrity risks the sanitation sector really faces, and turn things around. Reducing corruption and integrity risks is everyone’s business. It is an important part of good management. And, there are many ways to act, preventively and effectively.

Corruption and poor integrity in sanitation: how it plays out and how it affects our work

Many people have come across corruption, malpractice and integrity challenges in the sanitation sector. There are the complicated and potentially corrupt real-estate deals that underpin the construction of an FSTP plant in a specific location; the expensive treatment plant that never operates at full capacity; the bribes paid to avoid fines or get a favourable measurement at a weighing station; the manipulation of data on service provision to name but a few.

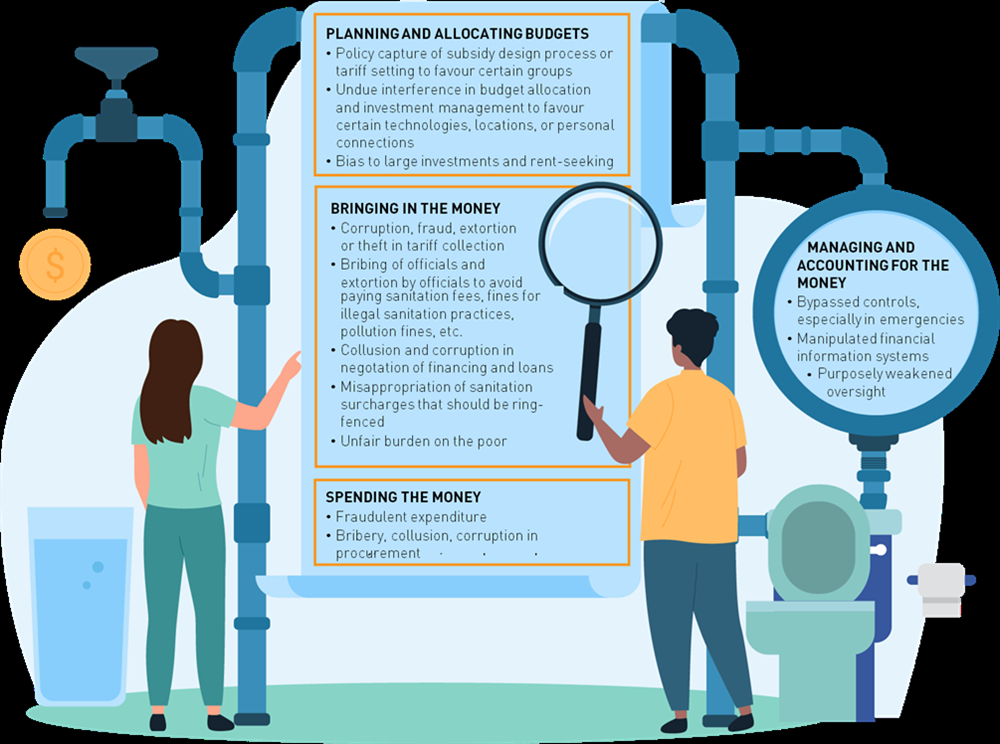

Procurement and contract management is often highlighted as a key risk area. And indeed, tendering processes geared to favour friends and family, suppliers bribing or colluding to get construction contracts, contractors using sub-standard materials are common issues. The Water Integrity Global Outlook: Integrity for Water and Sanitation Finance (WIGO: Finance) shows that there are risks across the project cycle, not just in the procurement phase, including right up front in the planning phase.

WIGO: Finance also shows how such corruption and poor integrity impact on sanitation and our ability to meet the target of universal access to safely managed sanitation. Sanitation is dignity and it does have a price tag. Someone always pays. Generally, the poor pay more and the unconnected -literally and figuratively- pay more, also with their time and health. The result is unsustainable and unjust.

To progress on SDG6 and do our job well in ensuring decent sanitation services for all, we must take into account the issues that divert money away from those who need it most. And it is everyone’s job.

Authorities outside the sector may indeed be deciding on specific procurement rules or responsibilities. But the way we manage data, report or turn a blind eye, decide on how to allocate budgets, account for money spent, decide who we hire – that is our responsibility. This responsibility and the effectiveness of action by the sector and in the sector is a key takeaway from a new book on sector-based action against corruption.

Integrity Risks in Finance for Sanitation throughout the Budget Cycle (source: WIN, adapted from WIGO)

Sanitation and sanitation finance are at high risk

Sanitation doesn’t get the attention it deserves. The lack of visibility, and the ‘taboo’ topic make it a prime target for possible shady deals and exploitation. The involvement of many stakeholders across the value chain, including public, private large, very small, informal and informal contractors means complexity, vulnerability, and risk. In many parts of the world, sanitation workers are poorly managed, mistreated, and poorly protected.

Our research on integrity risks across the sanitation value chain, from containment to treatment, disposal, and reuse, confirms there are major accountability that put the sector at risk. Financial and institutional arrangements for non-sewered sanitation are less formal or structured, even though they reach a large part of the population. Responsibilities for sanitation are often fragmented and hard to track. It is for example common for a mandate for service to be split between a national utility with responsibility for sewered sanitation and local government with responsibility for non-sewered sanitation.

There are also major regulatory gaps. Regulation for non-sewered sanitation is very limited or still barely nascent in many regions of the world. Sludge and wastewater treatment, disposal and reuse is also poorly regulated in many regions.

“The first red light is that there's always a moment, in the process of collecting financial data, where we hit a wall. There's always a part of the expenditure we cannot get information on, even though we know it has been done because we cross check with other databases. For example, we know there has been specific loan or grant, but we can't find where in the government budgets or institutions that loan or grant comes in.

I can also tell you, I thought this was random, but there's a pattern going on here. This usually happens with the sanitation sub-sector in urban areas. You can take note.”

- Catarina Fonseca, IRC Associate, speaking at the launch of WIGO: Finance on 11 Sept. 2024

The many ways sanitation practitioners can act, through three pathways for change – no reason, no room, no reprieve

There are many measures possible to support anti-corruption and integrity efforts. This is where sanitation actors can show innovation, learn from other sectors, assess priorities, and test new measures to strengthen their programmes and build a culture of integrity. New technology can be a powerful tool to better detect risks and issues, to close loopholes, manage data, and communicate transparently.

Recognising that past anti-corruption work often focused too narrowly on sanctions and deterrence, WIGO: Finance proposes three broad pathways and types of measures for change: no reason, no room, no reprieve:

- The “No reason” pathway is about finding ways to change the social norms that help rationalise corruption. It is about encouraging integrity by fostering ethical leadership, rewarding accountability, and promoting awareness about the negative impacts of corruption.

- The “No room” pathways is about limiting discretion, streamlining processes to prevent risk, and ensuring transparency. Procurement rules can play role. Engagement with civil society to target interventions and build trust as well.

- Finally, the "No reprieve" pathway emphasises detection of red flags and corrupt acts, as well as punishment. Whistle-blower protection as well as processes, capacity, and technology for detection are important elements.

By combining these pathways to address corruption and integrity challenges head-on, we can make a difference in the sanitation sector. With honesty and collaboration, especially with civil society and users, we can ensure that investments in sanitation lead to sustainable, equitable outcomes, for all.